Thread 1

Tajweed is an innovation

There are TV shows where the viewers call and recite the Quran only for the Quran teacher to chase them on the tiniest microscopic details in pronunciation and Tajweed. They make reciting the Quran harder than rocket science. This obsession over Tajweed and pronunciation has become the standard in Quran teaching today. But all this is an innovation.

It may seem to you that Tajweed is unanimously agreed upon by Muslim scholars. But in reality it isn’t. Traditional Saudi scholars don’t use Tajweed and they say Tajweed isn’t mandatory.Listen to this recitation by Bin Baz the most prominent modern Saudi scholar and notice how he skips most of Tajweed rules. He even pronounces theض as ظ which is a big no-no in Tajweed that some Tajweed scholars say it makes your prayer unacceptable!.Ibn Uthaimin is the second in prominence after Bin Baz. And he too recites without Tajweed. Listen to his recitation as an Imam in the grand mosque of Mecca:

Abdul Aziz Aal Al-sheikh, the current grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, also skips most of Tajweed

From Bin Baz’s website: He was asked about reading the Quran without Tajweed, He answered: (( No problem in that. If he reads it in (correct) Arabic then no problem to read without Tajweed if he pronounces the letters clearly even if he doesn't know how to do Idgham, Tarqiq or Izhar (Tajweed rules) or such. Because these things are just preferable. I mean Tajweed is preferable and it improves the recitation. But it's not mandatory. ))binbaz.org.sa/mat/19543

In this video, the Saudi scholar Saleh Al-Fozan was asked about Tajweed. He answered that Tajweed is just an improvement and that one must only avoid making grammatical errors.

The Saudi scholar Sa'ad Al-Husain has a stronger opinion: ((These so called (Tajweed) rules are an innovation that were not sanctioned neither by god nor his messenger. So it's forbidden to impose it (on others).)) He also says:((One of god's blessings on this country and the Saudi Dawah is that I don't know anyone of its scholars -from Muhammad Bin Abdul Wahab (d.1729) to Muhammad Bin Ibrahim Al-Sheikh (d.1969) - who used Tajweed or called for it. Ibn Baz was the only one who wanted to learn Tajweed but none of his religious masters (sheikhs) knew Tajweed so he learned it from a non-Arab. Nevertheless, Bin Baz didn't use Tajweed. And you can hear his innate recitation on the Internet and it's the best recitation I have heard.)) Source

Criticism of Tajweed isn’t new. Ibn Taymiyah (d.1328) is highly revered by Salafi Muslims that he’s called “The sheikh of Islam”. He says: ((One shouldn't put his effort into what blocked most people from realizing the truths of the Quran, which is the obsession over letters' articulation and Tarqiq, Tafkhim, Imalah, (Tajweed rulings) and the different kinds of vowel prolongation or such things that prevent you from understanding the word of god. ))

The medieval scholar Ibn Al-Jawzi wrote a book titled The tricks of the devil. He says in it: ((The devil tricks a worshipper with letters’ articulation. So you see a worshipper saying Al-Hamd, Al-Hamd. With this repetition driving him away from the manners of ritual prayers. The devil also tricks him in the articulation of the explosive nature of theض in المغضوب .I saw someone spitting from how strongly he articulated it.The devil makes the likes of him occupied with over-articulation preventing them from realizing the meaning of the recitation.))That’s what Al-Jawzi said 900 years ago. But today who needs the devil’s tricks when we have all these Quran teachers who make you obsessed with molecular-level details?

Thread 2

A refutation of traditionalists’ claim that the Quran was orally mass-transmitted

In this thread I am refuting traditionalists’ claim that the Quran was perfectly transmitted to us through oral mass-transmission by chains of reciters that go back to the prophet. This claim has become the scarecrow used by traditionalists to reject anything that challenges their presumed perfect preservation of the Quran. It’s their main argument against Sanaa manuscripts, narrations of scribal mistakes in the Quran, narrations of non-Uthmanic readings, and other challenging narrations such as that Ibn Masud removed the last two Surahs from his Quran and Ubay added two Surahs to his. Their extraordinary claim not only lacks evidence, but the evidence is actually against it:

1-The absence of Tajweed from the traditional Saudi school of thought.

2-The loss of the original sounds of the letters ض and ق .

3-The fact that the reading of Hafs was unknown to a major early Quranic scholar like Al-Tabari.

1-Quran scholars consider Tajweed to be an essential part of Quran recitation.Yet Tajweed until recently was unknown in Saudi Arabia the homeland of Islam where you would expect the oral transmission of the Quran to be the strongest.Traditional Saudi scholars don’t use Tajweed.

When the former grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia Bin Baz wanted to learn Tajweed, he learned it from a non-Arab because none of his religious masters knew Tajweed. Traditional Saudi scholars to this day recite the Quran without Tajweed. See my previous thread.

2-This “perfect” oral transmission that has supposedly preserved the finest details of Tajweed and Qira’at has actually failed in a much easier task: preserving the sounds of Arabic letters. Arab linguists unanimously agree that the modern sound of ض doesn’t match

early grammarians descriptions. The Iraqi linguist and Quran scholar Ghanim Qadduri says: ((While linguists unanimously agree that a change has happened to the pronunciation of ض . And while they strongly suggest that a similar change has also happened in the pronunciation of ط.

Another linguist, Husam Al-Ni'aimi, says: ((What we conclude is that the sound that undoubtedly changed in standard Arabic is the ض . All the rest of debated sounds are open to research although it's more likely that they haven't changed.))

3-Aasim عاصم is a master of one of the ten canonical readings. He had two narrators: Shu'ba and Hafs. The two narrations have many differences between them. Today the reading of Aasim according to the narration of Hafs is the most popular Quran reading.

Hafs’s reading has some unique variations that don’t exist in any other reading. Al-Tabari who lived in the third century of Islam wrote the earliest comprehensive interpretation of the Quran, wrote the first comprehensive Islamic history book and also wrote a book on the reading traditions (which is lost). Yet by reading his Tafsir it becomes clear that he never heard of the unique variations in Hafs’s reading, which are supposed to be orally mass-transmitted to us from the prophet according to traditionalists. Example:

Verse 70:16 in the reading of Hafs has the word نَزَّاعَةً nazzaa’atan in the accusative case (ends with "an").

While all the rest of reading traditions have it in the nominative case: nazzaa’atun (ends with "un").

Al-Tabari says in his interpretation of this verse:((It's grammatically correct to read نزاعة in the accusative but it's not permissible to read it like that because all reading masters read it in the nominative. No reading master read it in the accusative.)).

Thread 3

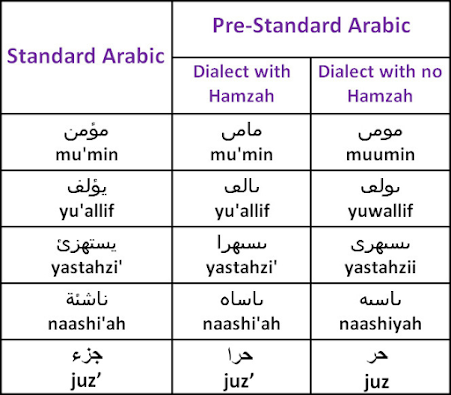

The Hamzah mess in Arabic orthography. The sign for a hamzah (glottal stop) in Arabic is ء which was created in the second century of Islam. But the hamzah in Arabic writing is rarely written with the hamzah sign ء alone.In most cases, the hamzah is written by adding the hamzah sign to one of the three vowels letters like this: أ ؤ ئ In Arabic, the letter for a long ‘a’ vowel is Alef ا . As in: kitaab كتاب The letter for a long u vowel and the 'w' sound is: و . As in: ruuH روحAnd the letter for a long i vowel and the 'y' sound is: ي , يـ . As in: fii في All these different forms: ء , ؤ , ئ, أ are pronounced the same: a glottal stop. Writing the hamzah is the trickiest thing in Arabic writing. Many Arabs make mistakes with them.But why don’t we write the hamzah in all cases simply as ء alone?. Actually in old Arabic the hamzah used to be written as an Alef in all cases. The Alef used to represent a glottal stop or a long ‘a’ vowel. But nearly 25 years after the death of the prophet, the third caliph Uthman decided to create a standard copy of the Quran to put an end to disputes over the different readings of the Quran. He assigned the job to a team of scribes who belonged to the prophet’s tribe of Quraysh which lacks the hamzah in its dialect. The standard copy that Uthman assembled is called the Uthmanic Quran. All Qurans in the world today follow the exact script of the Uthmanic Quran except for signs that were invented later like the diacritics and the hamzah sign.Arabs who had the hamzah in their dialects used to write a word like ذئب thi’b as ذاب because the Alef was the letter for hamzah. But the scribes of the Uthmanic Quran wrote this word as ذيب because the dropping of the hamzah creates a long i vowel (thi’b => thiib)and thus the letter that represents a long i vowel (ي، يـ ) gets used instead of the Alef (ذيب <= ذاب). They also wrote a word like mu’min as مومن because the dropping of the humzah creates a long u vowel (muumin) so they used the letter that represents a long u vowel و.

Uthman sent copies of his standard Quran to 4 different regions of the caliphate. Arabs in these regions started basing their Arabic orthography on these Qurans. So an Arab who had the hamzah in his dialect started writing the word mu'min as مومن instead of مامن although he kept pronouncing the hamzah in it. One century later when the sign of the hamzah ء was created, those Arabs who had the hamzah in their dialects added the hamzah sign over the long vowels, turning words like مومن to مؤمن and يستهزي to يستهزئThat's why Arabic today writes the hamzah in four different shapes: ء, أ, ؤ, ئ. Arabic will make more sense and will be easier if it goes back to the good old days of "the hamzah is only an Alef." But tradition is tight!

Thread 4Internal rhymes as an evidence for Old Hijazi. I have discovered many internal rhymes in the Quran that only appear when read in Old Hijazi the original dialect of the Quran which lacked nunation (Tanween) and final short vowels in non-construct.In classical Arabic, final short vowels and nunation are only lost at pause (the end of utterance). E.g. : هذا بيتٌ كبير “haathaa baytun kabiir”. The word kabiir isn’t pronounced as kabiirun because it’s at the end of utterance.But then why doesn’t Arabic write the nunation of the word baytun? It's not at pause so it should be بيتن not بيت . Arabic scholars justify this by the rule of pausal spelling: Every word is spelled as it would be spelled when pronounced at the end of an utterance.So it doesn't matter that the word بيت isn't at pause in the last example. Every word is written as if it's at pause. That's why nunation isn't written in Arabic. This rule also explains other cases where the orthography goes against the pronunciation:The feminine ending written as ‘h’ instead of ‘t’: من الجنة والناس min al-jinnati wan-naas. (Quran) الجنة isn’t written as الجنت because at pause the word is pronounced as al-jinnah instead of al-jinnati.The accusative nunation written with an aleph: وَكَانَ اللَّهُ عَلِيمًا حَكِيمًا wakaan al-laahu ‘aliiman Hakiimaa (Quran) عليما isn’t written as عليمن because at pause the word is pronounced as ‘aliimaa instead of ‘aliiman.Long vowels that get attached to the final ‘h’ pronoun are never written: وعنده أم الكتاب wa’indahuu ummu l-kitaab (Quran) وعنده isn’t written as وعندهو because at pause it’s pronounced as wa’indah. and argue that these differences between orthography and pronunciation resulted from bringing the language of poetry to the recitation of the Quran. And later when reciting the Quran in the language of poetry became the norm, the pausal spelling rule was come up with to explain the mismatch between the Quran’s orthography and the recitation. Thus nunation was unwritten in the Quran not because of pausal spelling, but because the language of the Quran didn’t have nunation in the first place. Van Putten in his valuable book uses internal rhymes to prove this point. These internal rhymes in the Quran only appear when the pronunciation matches the writing. Van Putten listed 6 unique internal rhymes and pointed out the frequent scheme of the epithets of Allah which form verse-final internal rhymes in the shape CaCŪ/īR in pairs of two, as in: ghafuur raHiim. I looked up the entire Quran and found 34 unique internal rhymes. I listed most of them in the video. For the full list read my Arabic article on Old Hijazi.https://t.co/7MRkjawmXV?amp=1For more on Old Hijazi:

https://t.co/87touiENOf?amp=1

https://t.co/1ADcs8o0uM?amp=1

Thread 5

The fail and the success of the ten canonical readings of the Quran.

The ten readings have failed in preserving the original dialect of the Quran. I showed in a previous thread that old Arabic orthography used to write the hamzah (glottal stop) as an Aleph. But that changed after Islam because Arabs started basing their orthography on the Uthmanic Quran which was written in the dialect of Quraysh which lacked the hamzah.

In the Uthmanic Quran, wherever the hamzah is written as a و or ى, the و is supposed to be pronounced as a long "u" vowel or a “w”. And the ى is supposed to be pronounced as a long “i" vowel or a “y”. The word ملائكة is used in the Quran 73 times.

The hamzah in this word is written as ىـ (connected ى) so it should be pronounced as ‘y’: malaayikah. But none of the ten readings pronounces the word like that (except for حمزة in pausal positions which are very few). They all pronounce it with hamzah: malaa’ikah.

Which means in 73 places in the Quran, the ten readings go against the written pronunciation. And this is just one example.

Let’s take variations of the word yu’min:

يؤمن: يؤمنون، تؤمنون، مؤمن

By searching for the combination ؤمن in the Quran I found 405 results.

So we have 405 words of this type where the hamzah is written as و meaning it should be pronounced as a long "u" vowel. Remember that every reading of the ten has two canonical transmitters. So in total we have 20 canonical transmissions of the Quran. Only 4 out of the 20 transmissions pronounce the و in these 405 words as it’s written: a long "u" vowel. The rest, including Hafs the most popular reading today, pronounce the و in these words as a hamzah. From the prevalence of similar words in the Quran I can safely say that there are over a thousand words in the Quran where most of the reading traditions go against the writing by pronouncing the ى or و as a hamzah. Which is a big fail if we judge the readings based on how good they preserved the original dialect of the Quran. But this wasn’t the goal of the reading masters when it came to dialectal features. Their goal was to bring the prestigious language of poetry into the Quran. And this language has features that don’t exist in the Qurayshi dialect such as the use of Hamzah.

Khalaf, a master of one of the ten readings, says: ((Quraish doesn't use the hamzah. It's not in their language. The reading masters took the hamzah from non-Qurayshi Arabs.)).Also Qalun, one of the two canonical transmitters of the reading of Naafi', said: ((The people of Medina never used the hamzah until Ibn Jundub used it in the words mustahzuun مستهزون and istahzi استهزي.))

Today, the non-Qurayshi features are taken by Arabs for granted as integral features of the Quran. If you read the Quran according to the Qurayshi dialect and pronounce the word ذئب as thiib (instead of thi'b), and عليهم as alayhum (instead of alayhim), an Arab would say this is colloquial and not “high Arabic”. How can the reading masters be more successful than this in bringing the poetry language into the Quran?. If we bring into the equation other features of the original Quranic dialect as reconstructed by Van Putten and Al-Jallad (Old Hijazi), then the reading masters’ success becomes epic because it’s beyond unthinkable to an Arab today that the Quran originally had a reduced case system and didn’t have Tanween. Read this comment (from the Arabs subreddit) on the video where I showed that reciting the Quran in Old Hijazi produces internal rhymes: ((It's funny how tanween (and case, and hamza) is so strongly associated since childhood with high, 'elevated' Arabic, that even though I can see the Old Hijazi reading produces consistent rhymes, and is probably how these ayāt were first composed, I still prefer the Hafs reading The Old Hijazi reading returns the Qur'an back to the worldly, mundane world of the colloquial.))

For more on how the language of poetry was introduced into the Quran:

https://t.co/bR7PJiIJt5?amp=1

Thread 6

It's strange that with all the obsession Islamic scholars have with following the footsteps of the prophet in everything, they never care about following the prophet in a crucial thing like the recitation of the Quran.

Instead they choose to follow the Quranic reading traditions that don’t represent the prophet’s dialect. Which reminds me of how Muslims used to strictly follow one of four Islamic schools of thought attributed to 4 scholars from the second and third Islamic centuries.

These 4 schools were so strictly followed that the grand mosque of Mecca for many centuries used to have a praying corner محراب for each of the 4 schools. Meaning that the followers of every school performed their own prayers in separation from the rest. So a Hanafi would only pray behind a Hanafi Imam. And a Hanbali would only pray behind a Hanbali Imam...etc. In this old image of the grand mosque of Mecca you can see the four praying corners where Imams from the 4 schools lead the prayer.

But nowadays the four schools of thought have greatly faded away. The norm today is basing Islamic jurisprudence directly on prophetic sayings instead of the opinions of the four Imams which in many cases contradicted with the prophet’s sayings.

The same thing should happen with the Quran.

Quran scholars are fully aware that none of the ten readings represents the original way the Quran was recited.

Al-Dani (d.1053 AD) was a major Quran scholar whose works are cited in modern Qurans as a source for the way the Quran is written. This modern Quran’s intro says: “The script is written according to the description of Al-Dani and Abdu Dawud Sulayman.”

Now let’s see what Al-Dani says in his book: ((Most of the (Uthmanic) script is written without the hamzah (glottal stop) in accordance with the dialect of Quraish which was the dialect of those who scribed the Quran at the time of Uthman)).

But none of the ten reading traditions represent a dialect that lacks the hamzah. We also know from a narration in Al-Bukhari that the prophet never had the rules of Tajweed in his recitation because he over-prolonged vowels that shouldn’t be over-prolonged according to Tajweed.

He over-prolonged all the long vowels in the Basmalah. Whereas Tajweed says only the long vowel of the last word in Basmalah can be over-prolonged.

sunnah.com/bukhari/66/70

So in the same way Muslims used to strictly follow the jurisprudence opinions of four Imams even when their opinions clashed with prophetic sayings, Muslims today are still doing the same thing with the Quran. They are strictly following the readings of ten Imams even though these readings clash with the Quran’s script which clearly lacks the hamzah.

Thread 7

A glaring contradiction in the canonical Quranic readings.

The reading traditions don’t only differ in dialectical features like glottal stops and Imalah. There are variants in these readings that affect the meaning. And in a some cases, the meanings are contradictory.

The best example of this kind is the last example in the list here:

https://t.co/b8IpgVctcn?amp=1

Let me explain it:

Lut's city was about to receive God’s punishment. Lut’s wife wasn’t a believer. So the angels told Lut to take his family and leave the city in the night. But there was an exception regarding Lut’s wife.

And that’s where the readings contradict each other.

From the blog post:

((In verse 11:81 Lot is told two conflicting instructions by the angels depending on the reading. Ibn Kaṯīr and Abū ʿAmr read ʾilla mraʾatuka (except your wife) in the nominative case, meaning that Lot must set out with his whole family but not let anyone except his wife look back. The others read ʾilla mraʾataka in the accusative case, meaning that Lot must set out with his family except his wife, leaving her behind.))

Here’s the verse according to the canonical readings of Ibn Kathir and Abu Amru:

((So set out with your family during a portion of the night and let not any among you, except your wife, look back; indeed, she will be struck by that which strikes them.))

And here’s the verse according to the rest of the canonical readings including the standard reading today:

((So set out with your family, except your wife, during a portion of the night and let not any among you look back; indeed, she will be struck by that which strikes them.))

The contradiction here is that according to the first reading (illa mra'atuk), Lut took his wife with him and she left the city. She died when she looked back. But according to the second reading (illa mra'atak) Lut didn’t take his wife and she stayed in the city and died in it.

Al-Tabari (d. 310 AH) who wrote the earliest comprehensive interpretation of the Quran says:

((The majority of the reading masters of Hijaz, Kufah and some in Basrah, read it in the accusative: illa mra’atak. Meaning: Set out with your family except your wife.

So Lut was ordered to set out with his family except his wife leaving her with her people.

And some reading masters in Basrah read it in the nominative: illa mra’atuk. Meaning: Not any among you, except your wife, look back. So Lut took her out with him.

And he and his family were ordered not to look back except his wife. She looked back and that’s why she died.))

https://t.co/JfiTYlWqsp?amp=1

Al-Zamakhshari (d. 538 AH) says in his interpretation:

((There are two narrations on how he set out with his family: It was narrated that he took her out with his family and was ordered that none of them should look back except his wife. So when she heard the loud noises of the punishment she looked back and said: “O my people!”. So she was hit with a stone killing her.

And it was also narrated that Lut was ordered to leave her with her people given that she supported them. So he didn’t take her out. The different narrations caused the different readings.))

Notice how Al-Zamakhshari had no problem in pointing out that the conflicting narrations caused the conflicting readings. Which affirms that early Muslim scholars didn’t believe in the perfect preservation of the Quran which was clearly reflected in their numerous criticisms of the reading traditions. But today traditional scholars would instantly try any apologetic gymnastics possible to refute this contradiction and happily declare that the Quran is indeed perfectly preserved and that infidels and orientalists have been utterly destroyed.

But if you go back in time to the early centuries of Islam and tell any scholar that the reading traditions aren’t entirely divine and that many reading variants were introduced by humans, the scholar would say: No shit.

I got replies saying that Quran exegetes have an explanation for the contradiction. The thing is: In Arabic grammar anything can be justified. You can break any basic grammatical rule and find a justification for it if you have the will.

What matters here is that the straightforward grammar of the two readings yields a contradiction.

The early exegetes Al-Fara’, Al-Tabari, Al-Akhfash and Al-Zajjaj all explained the two readings according to the straightforward grammar which yields the contradiction. None of them tried any forced interpretation to resolve the contradiction.

Later exegetes started to take a non-straightforward path in interpretation or grammar because they started to believe that the two readings are divine and so they cannot be contradictory. Some of them actually clearly stated this reasoning like Abu Hayyan Al-Andalusi (d. 745).

He quotes what Al-Zamakhshari said then comments: ((This is a huge mistake. He made the two historical reports that say Lut took her with him or didn’t take her, he made them the origin of the two readings.

Such a contradiction in the historical reports cannot exist in the two readings which are the words of god.))

So later exegetes started to force solutions due to theological reasons. So when they bring the theological aspect, then I too have the right to bring the theological aspect and point out the problem that arises from their forced solutions:

Since that the straightforward meaning of the two readings is contradictory, why did god reveal the verse in these two readings when he knows that people will think there's a contradiction between god's words?. Why didn’t he just reveal the verse in one reading?.

Thread 10

My response to Ammar Khatib's response

He says regarding some early scholars’ rejection of some readings: ((these scholars were not questioning the authenticity of the Qur'anic text but rather the transmission of the reading

Thread 11

Part 2 of my response to Ammar Khatib:

To remind you of the contradiction:

Here’s verse 11:81 according to the canonical readings of Ibn Kathir and Abu Amru which have “except your wife” in the nominative:

((So set out with your family during a portion of the night and

let not any among you, except your wife, look back; indeed, she will be struck by that which strikes them.))

to the nominative reading. Exegete Abu Hayan Al-Andalusi (d.745 AH) quoted Abu Shamah and rejected his take by saying this sort of disconnected exception must always be in the accusative so it cannot apply to the nominative reading.

Khatib: ((Another good explanation is that it's possible that the wife of Lut followed her household but she didn't complete the journey and she looked back and got destroyed. According to this explanation, Lut didn't take her with him...she attempted to follow them and wasn't able to complete the journey because she got destroyed. ))

With this type of forced justification anything can be justified.

Ibn Zanjalah (d.403), in his book on the meanings of the disputed readings, reports that the reading master Abu Amru read in the nominative because Abu Amru took the interpretation that Lut set out with his wife.

Finally let me reiterate that the straightforward understanding of the two readings yields the contradiction. The early exegetes Al-Fara’, Al-Tabari, Al-Akhfash and Al-Zajjaj all explained the two readings according to the straightforward grammar which yields the contradiction.

Later exegetes started to take a non-straightforward path because they started to believe that the two readings are divine.The most common solution later exegetes came up with is that the accusative reading can grammatically be an exception from “let not any among you look back” thus both readings mean the same thing. Aside from it being non-straightforward, there are two issues with this solution:

1- Many exegetes admit it’s grammatically less eloquent for the accusative reading to be an exception from “let not any among you look back”. Which means that the majority of the canonical readings are on the less eloquent reading. Al-Hasan Bin Ahmad (d.377) is the first one I know of who pointed out that it’s grammatically possible for the accusative reading to be related to “let not any among you look back”. But he also states that in this case the nominative reading is the eloquent one.2- This solution is against the non-Uthmanic reading of the prophet’s companion Ibn Masud who said that he knows no one who’s more informed in the Quran more than him. In his reading the verse is: “So set out with your family except your wife during a portion of the night".The part “let not any among you look back” is missing. So there’s no way for “except your wife” but to be related to “set out with your family”. Many exegetes, like Al-Qurtubi, used Ibn Masud’s reading to confirm the meaning of the accusative reading.